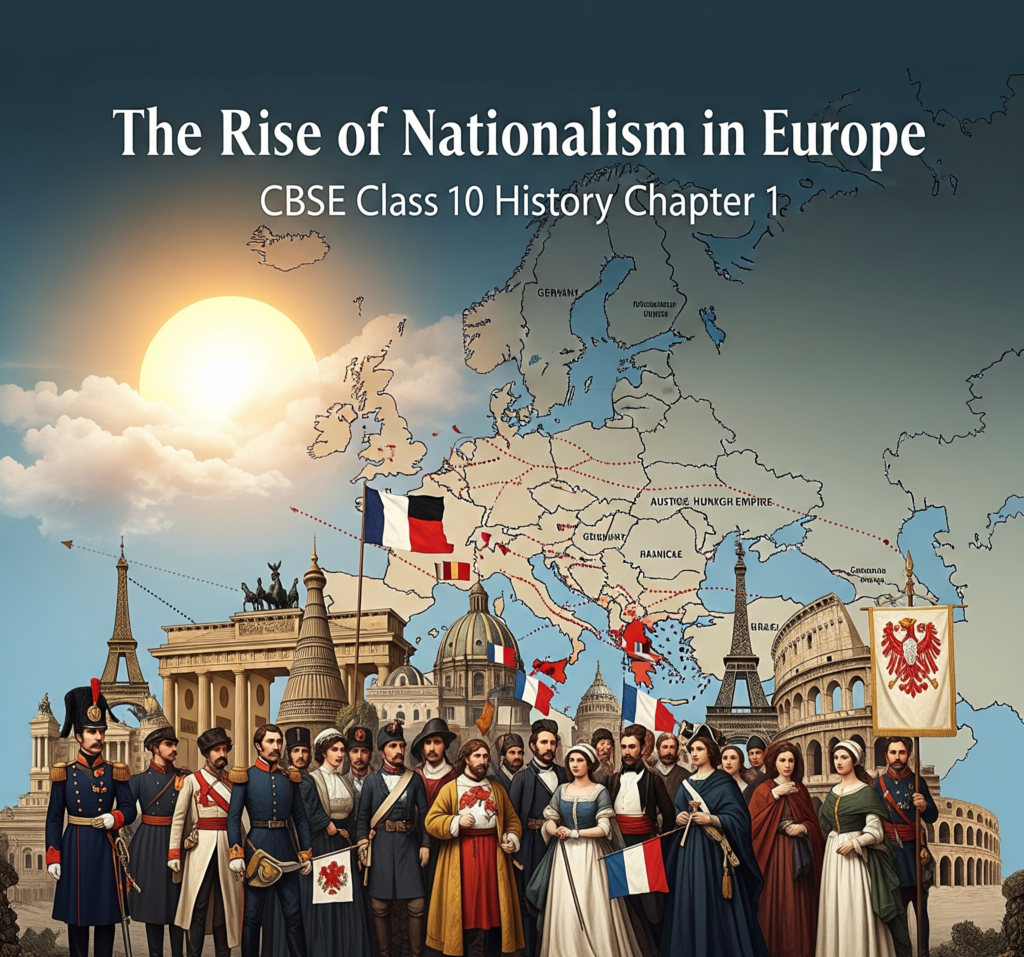

Here are the comprehensive The Rise of Nationalism in Europe Notes, based primarily on the NCERT textbook for the CBSE Class 10 History syllabus, Chapter 1. These notes cover all key concepts of the chapter, including the symbolism of Frédéric Sorrieu’s prints, definitions of nation and nationalism, the impact of the French Revolution, the Napoleonic Code, political and social changes in 18th-19th-century Europe, liberal nationalism, conservatism after 1815, and the role of revolutionary figures like Giuseppe Mazzini. Designed to help you grasp each topic clearly, the notes include simple explanations, key terms, important events, and relevant historical context. Whether you are revising for exams or building a strong foundation, this chapter summary is your quick and reliable guide.

The Dream of Worldwide Democratic and Social Republics

- In 1848, the French artist Frédéric Sorrieu created a series of four prints to visualize his ideal world of “democratic and social Republics”.

- The first print shows people from Europe and America, of all ages and social classes, marching in a long procession and paying homage to the Statue of Liberty.

- The Statue of Liberty is personified as a female figure, holding the torch of Enlightenment in one hand and the Charter of the Rights of Man in the other.

- The ground in the foreground contains the broken symbols of absolutist institutions.

- In Sorrieu’s utopian vision, people are grouped by distinct nations, identifiable by their flags and national costumes. The procession is led by the United States and Switzerland, which were already nation-states at the time. France, identified by its tricolour flag, has just reached the statue, and is followed by Germany (with a black, red, and gold flag), Austria, the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies, Lombardy, Poland, England, Ireland, Hungary, and Russia.

- From above, Christ, saints, and angels observe the scene, symbolizing the fraternity among the world’s nations.

- Key Terms:

- Absolutist: A government or system of rule with no restraints on power. Historically, it refers to a centralized, militarized, and repressive form of monarchical government.

- Utopian: A vision of an ideal society that is unlikely to exist in reality.

Defining a Nation

- The French philosopher Ernst Renan, in his 1882 essay ‘Qu’est-ce qu’une nation?’ (‘What is a Nation?’), criticized the idea that a nation is formed by a common language, race, religion, or territory.

- He argued that a nation is the result of a long past of efforts, sacrifice, and devotion.

- A nation is a “large-scale solidarity” based on a heroic past, common glories, a shared will in the present, and a desire to perform great deeds together.

- He believed that the existence of nations is a good thing and a necessity, as it guarantees liberty that would be lost if the world had only one law and one master.

1. The French Revolution and the Idea of the Nation

- The first clear expression of nationalism was the French Revolution in 1789, which transferred sovereignty from the monarchy to a body of French citizens.

- Revolutionaries created a sense of collective identity through various measures:

- The ideas of la patrie (the fatherland) and le citoyen (the citizen) emphasized a united community with equal rights under a constitution.

- A new French tricolour flag replaced the royal standard.

- The Estates General was renamed the National Assembly.

- New hymns were composed, oaths were taken, and martyrs were commemorated in the name of the nation.

- A centralized administrative system with uniform laws was established.

- Internal customs duties and dues were abolished, and a uniform system of weights and measures was adopted.

- Regional dialects were discouraged, and French became the common language of the nation.

- The revolutionaries believed it was the French nation’s mission to liberate the peoples of Europe from despotism.

- News of the French Revolution led to the formation of Jacobin clubs across Europe, preparing the way for French armies to carry the idea of nationalism abroad.

- The Napoleonic Code (Civil Code of 1804):

- Napoleon, while destroying democracy, made the administrative system more rational and efficient by incorporating revolutionary principles.

- The Code abolished privileges based on birth, established equality before the law, and secured the right to property.

- It was exported to regions under French control, simplifying administrative divisions, abolishing the feudal system, and freeing peasants from serfdom.

- However, the new administrative arrangements were often opposed due to increased taxation, censorship, and forced conscription.

2. The Making of Nationalism in Europe

- In mid-eighteenth-century Europe, there were no nation-states. Germany, Italy, and Switzerland were divided into kingdoms and territories, and Eastern and Central Europe were ruled by autocratic monarchies with diverse populations.

- The Habsburg Empire, for example, was a patchwork of regions where people spoke different languages (German, Italian, Magyar, Polish) and belonged to different ethnic groups, with the only unifying tie being allegiance to the emperor.

2.1 The Aristocracy and the New Middle Class

- The landed aristocracy was the dominant class, united by a common lifestyle and speaking French for diplomacy. They were a small group, while the majority of the population was peasantry.

- The growth of industrial production led to the emergence of new commercial classes and a working-class population, as well as industrialists, businessmen, and professionals who formed the new middle class.

- It was among the educated, liberal middle classes that ideas of national unity gained popularity, following the desire to abolish aristocratic privileges.

2.2 What did Liberal Nationalism Stand for?

- The term ‘liberalism’ comes from the Latin root liber, meaning ‘free’.

- Political Ideals:

- Freedom for the individual and equality before the law.

- Government by consent, a constitution, and a representative government through parliament.

- The end of autocracy and clerical privileges.

- The inviolability of private property.

- However, equality before the law did not mean universal suffrage; voting rights were often limited to property-owning men, and women were excluded from political rights.

- Economic Ideals:

- Freedom of markets and the abolition of state-imposed restrictions on the movement of goods and capital.

- In the German-speaking regions, Napoleon’s measures had created a confederation of 39 states, each with its own currency and system of weights and measures, which were seen as economic obstacles.

- To address this, a customs union called the Zollverein was formed in 1834 at the initiative of Prussia, which abolished tariff barriers and reduced the number of currencies from over thirty to two.

- The creation of railways further stimulated mobility and strengthened economic nationalism, which in turn fostered wider nationalist sentiments.

2.3 A New Conservatism after 1815

- After Napoleon’s defeat in 1815, European governments embraced conservatism, a philosophy that favored preserving traditional institutions like the monarchy, the Church, and social hierarchies.

- Conservatives believed that modernization could strengthen these traditional institutions by creating a modern army, an efficient bureaucracy, and a dynamic economy, and by abolishing feudalism and serfdom.

- The Treaty of Vienna (1815):

- Hosted by Austrian Chancellor Duke Metternich, the Congress of Vienna aimed to undo the changes brought by the Napoleonic Wars.

- The Bourbon dynasty was restored to power in France, and France lost its annexed territories.

- A series of states were created on France’s borders to prevent future expansion.

- The main goal was to restore monarchies and establish a new conservative order in Europe.

- Conservative regimes were autocratic, did not tolerate criticism, and imposed censorship laws to control ideas of liberty and freedom associated with the French Revolution.

2.4 The Revolutionaries

- Following 1815, the fear of repression led liberal-nationalists to go underground and form secret societies to train revolutionaries and spread their ideas.

- Revolutionaries sought to oppose monarchical forms of government and fight for liberty and freedom, often seeing the creation of nation-states as a necessary part of this struggle.

- Giuseppe Mazzini:

- An Italian revolutionary born in 1805, he was a member of the secret society of the Carbonari.

- After being exiled in 1831, he founded two more underground societies: Young Italy in Marseilles and Young Europe in Berne.

- Mazzini believed that nations were the “natural units of mankind” and that Italy needed to be forged into a single unified republic.

- His opposition to monarchy and his vision of democratic republics made him a target of conservatives, and Metternich described him as “the most dangerous enemy of our social order”.