Few events in the complex history of India’s freedom struggle solidified the anti-colonial sentiment and intensified the nationalist impulse. The Simon Commission of 1927-1928 is one of these important episodes. As a student of colonial history, I have always found it interesting to see how this general administrative commission became the focal point of nationalist resistance and helped consolidate Indian political unity against British rule.

Origin and Context

The Indian Statutory Commission, popularly known as the Simon Commission after its chairman Sir John Simon, was appointed by the British government in November 1927 to examine the operation of the Government of India Act, 1919. This law promised the gradual development of autonomous institutions in India, to be reviewed after ten years. The commission comprised seven members of the British Parliament, but surprisingly, there was no Indian among its members.

This exclusion proved to be a grave strategic error. By 1927, Indian political consciousness had grown considerably since the implementation of the Act. The Indian National Congress, the Muslim League, and other political organisations had matured enough for their leaders to be able to present a sophisticated constitutional vision for India’s future.

The Boycott Movement

The all-European composition of the Commission immediately provoked widespread resentment throughout India. The message was clear: Indians were unfit to determine their own constitutional future. As Congress leader Motilal Nehru said, it was “not only an insult to the self-respect of India but a denial of the principle of self-determination.”

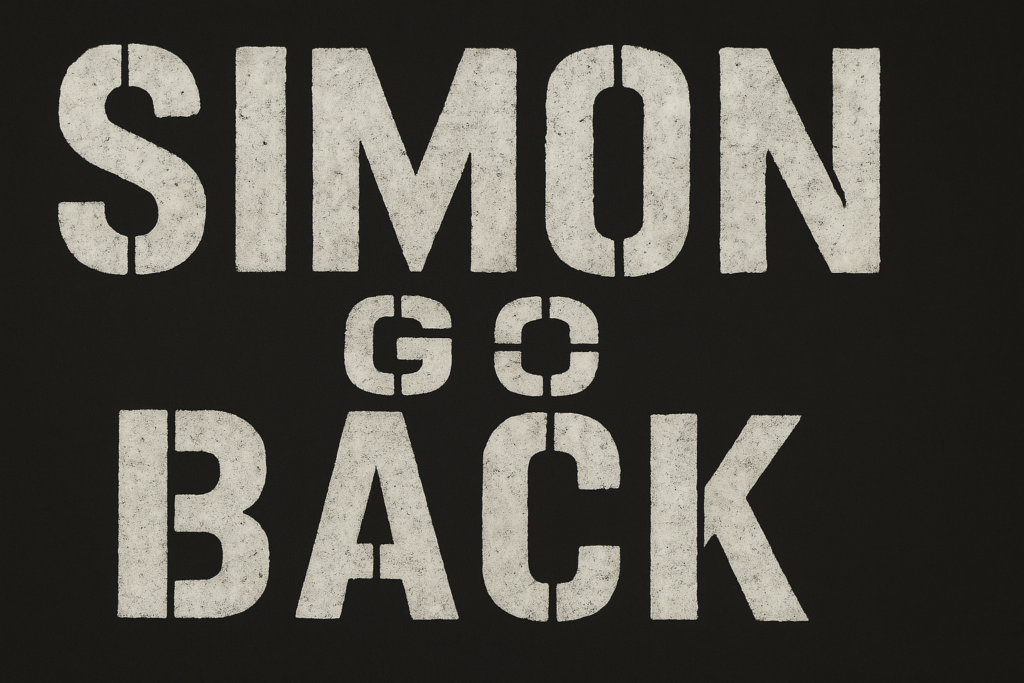

The response was swift and united. When the Commission arrived in Bombay (now Mumbai) on February 3, 1928, it was greeted with black flags and slogans of “Simon, come back.” This pattern was repeated throughout India, with protests in major cities including Lahore, Madras (Chennai), and Calcutta (Kolkata).

Lahore incident and Lala Lajpat Rai

Probably the most significant demonstration took place in Lahore on 30 October 1928. A peaceful protest led by senior nationalist leader Lala Lajpat Rai was met with brutal police action. Lajpat Rai sustained injuries during the invasion of the monastery, which led to his death within three weeks.

His last words – “Every blow inflicted on me today is a nail in the coffin of British imperialism” – became the slogan of the independence movement. The incident transformed a political protest into an intensely emotional national movement. For many young revolutionaries, including Bhagat Singh, the attack on Lajpat Rai justified more revolutionary action against the colonial authorities.

Political significance

The boycott of the Simon Commission has historical significance at several levels:

- First, it was one of the few moments of unity between Hindus and Muslims during this period. Despite rising communal tensions, the Congress and the Muslim League initially showed solidarity by rejecting the commission.

- Second, it clearly demonstrated the evolution of Indian nationalism from petition to mass movement. These protests were not limited to the political elite but also involved ordinary citizens from all walks of life.

- Third, the Commission inadvertently accelerated India’s constitutional development. In response to the boycott, Indian leaders held an All India Party Conference, which produced the Nehru Report – India’s first major attempt to create its own constitution, advocating Dominion Status.

Personal View

What struck me most about the Simon Commission incident was how a simple bureaucratic process became transformative. The British government, still operating from an imperial mindset, failed to understand how much Indian political consciousness had developed. By excluding Indians from the commission that was to determine India’s constitutional future, they exposed the fundamental contradiction of colonial rule: the impossible promise to prepare the people for self-rule, while at the same time denying their capacity for self-determination.

The protests against the Simon Commission also highlight the power of symbolic politics. The “Go Back Simon” slogan and the display of black flags created a powerful visual image that expressed resistance more effectively than lengthy manifestos.